Henry James' Owen Wingrave: A Detailed Summary and Literary Analysis

- M. Grant Kellermeyer

- Aug 27, 2018

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 25, 2025

One of James’ darkest tales – exceeding “Romance of Certain Old Clothes” and rivalling Turn – “Owen Wingrave” has been his second-most commented upon ghost story, surpassing even “The Jolly Corner,” and shares the distinction with Turn of the Screw of having been made into a compelling opera by Benjamin Britten. The antithesis of the cycle-breaking Sir Edmund Orme, the spirits who haunt “Owen Wingrave” are hell-bent on preserving a ghastly, centuries-long pattern of destruction.

The story was inspired when James – who was reading the autobiography of one of Napoleon’s generals, and was at the time consumed with visions of glorious victories and gallant defeats – shared a park bench with an attractive young man: “A tall quiet studious young man had sat near him and settled to a book with immediate gravity.” Struck by the juxtaposition of the two things – the violent glories of battle and the gentle beauty of the young reader – James envisioned a world where his pretty companion was thrust into a predestined relationship with war.

“Owen Wingrave” is predictably riddled with homoerotic subtext, particularly in the relationship between Owen (whose name means “young soldier,” and whose morbid surname underscores his family’s celebration of wartime death), and his military tutor, Coyle.

Further queer elements exist between both men and the child-like (albeit stupid) youth Lechmere, and with Owen’s war-hungry on-again-off-again girlfriend, Kate (whom Coyle describes as a “brute,” and whose bloodthirsty machinations may or may not be designed to lure her lover to his death). Owen is depicted as a sensitive, poetry-reading, big-souled lad – a boy whose intellect and spirituality has (in Coyle’s mind) far surpassed that of his war-loving family members.

Coming from a military family, his refusal to complete his martial education arouses the disgust of his family, his girlfriend, and his ancestral manor. The story begins like a comedy of manners, or even as a Shakespearean romance: a youth must defy his family in order to pursue his heart, and is beset by a number of trials before he can achieve his desires.

Indeed, the first three chapters allow us the hope that this is a gentle comedy with a happy ending. But when the fourth chapter arrives, hope is rapidly lost. We venture into the Wingrave house – said to be haunted by his violent ancestors – and we see how Owen has aged after mere weeks. The family is determined to protect its martial lineage, and Owen’s dishonor cannot go unpunished. And yet, there is a twist – one that Coyle finds stirring and spiritual: Owen’s very defiance of his military future is in every way the behavior of a soldier. He is brave, manly, determined, self-possessed, and brimming with gallant character.

His seemingly inevitable assassination is therefore wrought with irony: for refusing to be a soldier, Owen will face death in a manner that can only be described as soldierly.

SUMMARY

Owen Wingrave, the last scion of a long line of soldiers, shocks his tutor and family by announcing that he will not become an officer. In London one afternoon he tells Spencer Coyle, the professional coach who has been preparing him for Sandhurst, that he has “quite decided” to give up the profession his family have treated as a sacred duty. Coyle reacts with disbelief and anger—“Upon my honour you must be off your head!”—and urges Owen to take time, to go to the seaside, to reconsider. Owen is steady: he says he has thought it all out and will not be bullied into a career he finds morally intolerable. He asks Coyle to keep the matter quiet and to delay judgment until he has faced his family; Coyle, proud of his pupil’s gifts and anxious for his reputation, agrees to try to help.

Coyle consults the other young men in his charge, notably the simple, loyal Lechmere, and finds that Owen’s decision has already begun to spread alarm. Lechmere is willing to plead with his friend as a comrade-in-arms; Coyle, whose life is given over to making soldiers, feels betrayed and baffled by Owen’s “intellectual independence.” He telegraphs Miss Jane Wingrave, Owen’s aunt, and soon goes to Baker Street to press the family’s authority. Miss Wingrave, a stern representative of the Wingrave military tradition, assembles a plan: bring Owen to Paramore, the family seat, and let the household—Sir Philip Wingrave, the old patriarch, Miss Wingrave herself, Mrs. Julian and her daughter Kate—remonstrate with him. Coyle accepts the invitation, and Lechmere and Mrs. Coyle accompany him to the house.

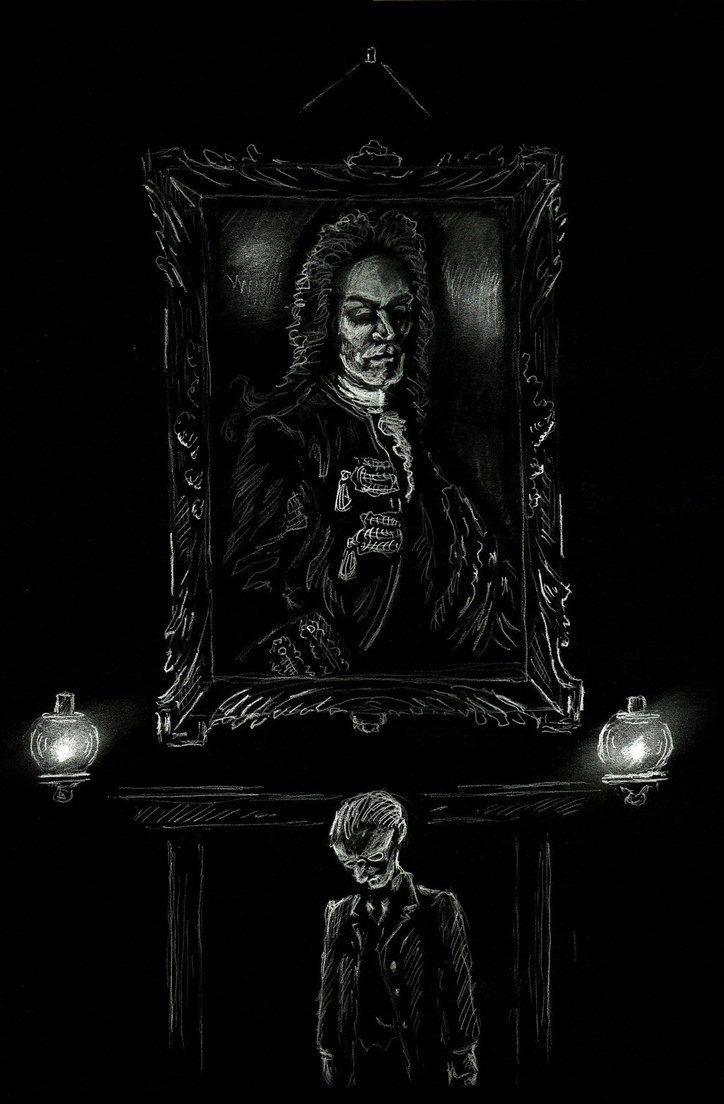

Paramore is an austere, decorous mansion filled with portraits, memory and military lore. There Coyle learns in more detail the family history: the Wingraves’ long record of service, the shrill morality of Miss Wingrave as guardian of that tradition, and the household legend of an old tragedy that haunts their name. Sir Philip, an octogenarian relic of campaigns abroad, presides with a warrior’s gravity. Mrs. Julian, a neighbor and dependent, and her daughter Kate—young, exotic in appearance and fearless in manner—are also present; Kate’s coquettish, sometimes insolent, behavior makes her a volatile figure in the household. Coyle senses both the severity of the house’s pressure and a curious sympathy with Owen’s courage in standing his ground against it.

Owen himself explains, calmly and with an almost ascetic resolve, why he refuses the military life. He speaks of the “general consciousness and responsibility” in the house that oppresses him; of the way portraits and family traditions seem to glare their expectations upon him; and of a moral revulsion at war. He tells Coyle that money and property mean little to him—he will lose his expected inheritance if he abandons the army, but he admits he does not care for that loss. “I don’t care a rap for the loss of the money,” he says; what troubles him is the pressure of the house and the sense that, by staying, he would be acting in bad faith toward his conscience. Still, his stubborn refusal provokes indignation in the family and leaves him exposed to social contempt.

The house has a particular story that gives the conflict a strange, ominous coloring. Generations earlier a Colonel Wingrave struck a son in a paroxysm of temper; the youth died; the Colonel was later found dead, apparently overcome by remorse or a supernatural visitation, in the room where the child’s body had lain. That chamber—panelled and painted white and long since known as the “White Room”—is taboo in the house; no one sleeps there and an old tale of apparition and sudden death clings to it. Guests are shown the portrait of the formidable ancestor who figures in the legend, and superstitions circulate in whispers.

During the visit social tensions intensify. Kate Julian, whose spirit is both mocking and daring, taunts Owen about his courage and his motives; she ridicules his scruples and insinuates he is using moralism as a pretext. In the drawing-room after dinner, the subject of the haunted White Room is revived; Lechmere, who admires Owen, presses him; Owen replies that he has even spent a night in the room—“I spent all last night in the confounded place,” he tells Lechmere—yet he has not boasted of it, and Kate jeers that if he had really done it he should have made “something good” of the story. In an exchange heating up between them Owen tells Kate to “Take me there yourself, then, and lock me in!” and the lovers—if they can be so called—streak their words with both challenge and intimacy. The talk ends with the household separating for the night, uneasy and watchful.

Later, in the small hours, catastrophe strikes. Spencer Coyle and his wife have both been restless; Mrs. Coyle, unnerved by the house and by Owen’s predicament, begs her husband to look in on the young men. Coyle falls asleep in his chair, but soon a terrified cry—“Help! help!”—breaks the midnight quiet. He rushes through the passages, and at a turn finds Kate Julian in a swoon on a bench; she has, on returning from an attempt to free or to find Owen, collapsed with a tragic cry. Coyle staggers on and through an open door encounters Owen Wingrave lying dead on the floor of the White Room, dressed as he had last been seen. The description is stark: he “looked like a young soldier on a battle-field.” There is no sign of external violence in the body; the hall is full of alarm, and Kate, riven by her own grief and terror, reels from the scene.

The household is thrown into confusion and horror. The discovery—Owen found lifeless in the very room associated with ancestral guilt and supernatural dread—brings the family’s moral and literal histories together in a single, devastating event. Guests and servants pour into the corridors; the old patriarch’s presence, the aunt’s rigid protocol, the jeers and taunts of the preceding hours all stand as raw contexts for the tragedy. The narrative closes on the immediate facts of that night: the waking cries, Kate Julian’s swoon, Coyle’s shock at the corpse in the White Room, and the sudden collapse of everything the family had counted as secure.

ANALYSIS

Like “The Ghostly Rental,” Henry James’ “Owen Wingrave” owes much to the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe, and in particular to “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Poe’s story dramatizes the fate of a family whose house is supernaturally grafted into its bloodline, its very stones saturated with hereditary doom. James echoes this conceit: the Wingrave mansion seems to possess a personality, a spirit, and a will of its own, inseparably sutured into the collective soul of the family.

It functions as both symbol and totem—a monument to generations of martial pride and slaughter—and its brooding presence becomes a sign of impending danger for the rebellious Owen. Both James and Poe explore the overwhelming power of historical inheritance: centuries of violence, conquest, and bloodshed accumulate into a near-irresistible current, a riptide that drags individuals back into the destructive destiny of their lineage. Owen, for all his ideals and personal courage, is ultimately engulfed and smothered by the momentum of his family’s militaristic past.

The story provoked fierce debate among James’ contemporaries, particularly among progressive critics. George Bernard Shaw, for instance, was scandalized by Owen’s defeat. Writing to James, he lamented: “You have given victory to death and [old-fashioned values]: I want you to give it to life and regeneration.” Shaw wanted Owen to embody the triumph of nonconformity, to prove that a refusal to submit to tradition could be rewarded rather than punished. James, however, rejected this outright. If Owen had survived, he argued, the narrative would have collapsed under its own weight: the inexorable logic of the tale demanded Owen’s death. James saturates the story with such fatalism that the ending feels both savage and inevitable. Owen is not simply defeated; he is destined for destruction from the moment he defies his heritage. This inexorability is part of what gives the story its haunting power.

II.

Yet “Owen Wingrave” is not a simple tract against conservatism or militarism. James complicates his narrative by blending progressive ideals—Owen’s principled rejection of violence—with a cynical recognition of the crushing persistence of traumatic cycles. The story becomes an emotionally complex parable of national sin, dramatizing how societies feed on the sacrifice of youth to sustain their corrupted values. This double vision—both hopeful and fatalistic—accounts for its timelessness. Indeed, Benjamin Britten’s opera adaptation has been staged in contexts ranging from World War II to the Vietnam War, from the Gulf War to the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The story’s resonance is not limited to Victorian Britain but applies across centuries and cultures: from the Spartan and Roman cults of martial sacrifice, through the Napoleonic Wars, the American Civil War, the wars of religion, and down to modern terrorism and insurgency. Its enduring moral can be summed up in the bitter maxim: “Old men declare war, but it is the youth who must fight and die.” Mary Roberts Rinehart sharpened the sentiment even further: “I hate those men who would send into war youth to fight and die for them; the pride and cowardice of those men, making their wars that boys must die.”

“Owen Wingrave,” in its emphasis on wasted youth, corrupted innocence, and discarded promise, anticipates the themes of All Quiet on the Western Front and other modern anti-war classics. But James’ tale is perhaps more unsettling than Remarque’s because Owen’s “execution” is not merely the result of impersonal military machinery; it is carried out with the virtually undeniable collusion of his own family. His grandfather, aunt, and fiancée act in harmony with the malignant spirits of the Wingrave house, goading Owen toward doom in order to preserve their honor and punish his insubordination. Like Usher, who is destroyed for breaking his family bond, Owen is executed for treason against his heritage.

III.

Despite Shaw’s protests, Owen’s death is not a pathetic defeat. Unlike Roderick Usher, crushed by his sister’s vengeance, Owen falls on a supernatural battlefield with a soldier’s bravery. In a bitter irony, he meets his family’s expectations of martial valor precisely through his steadfast rejection of their values. In refusing to be cowed by their taunts, he proves his manhood on his own terms, and in so doing, reveals the hollowness of their definition of courage.

Manhood is, in fact, a monomaniacal obsession in the story, and James layers his treatment of it with striking psychological nuance. Coyle, Owen’s tutor, seems to develop a deep attachment—bordering on a homoerotic crush—for his charge, an attraction that leaves his wife sidelined and shivering alone while he devotes his watchful energy to Owen. Meanwhile, Kate Julian, Owen’s fiancée, embodies a more brutal vision of masculinity. James even allows Coyle to strip her of feminine qualities, calling her a “brute”—a word more commonly applied to violent men. Through Kate, James exposes the Victorian conflation of courage, aggression, and social worth. At the heart of this lies the notion of “the gentleman.” In the nineteenth century, “gentleman” did not merely mean a man of polite manners. It was a caste identity, defined by pedigree, wealth, and reputation as much as by conduct. To be “no gentleman” was not simply to be rude but to be spiritually and socially inadequate—emasculated, dishonored, and excluded from one’s class.

The Wingraves define masculinity by martial courage. Their portraits celebrate men of violence—even murderers—while cowards are expunged from memory. For them, courage equals legitimacy; cowardice equals nonexistence. This obsession permeates the household. Lechmere, a girlish and weak-minded cadet, is terrified even to suggest that Owen may be a coward, for the word itself is emasculating. Kate, more vicious still, attacks Owen’s masculinity by daring him to sleep in the haunted chamber, fully aware—or at least suspecting—that she is sending him to his doom.

IV.

Yet Owen outdoes her and all the rest. Not only does he accept the challenge, but he calmly reveals that he has already spent nights in the chamber. He does not merely meet their test; he surpasses it, showing more courage than any of them are capable of recognizing. Owen emerges, in Coyle’s eyes, as the most mature, principled, and noble character in his family. His nightly return to the chamber resembles a soldier repeatedly taking his place on the battlefield, awaiting the enemy. In the end, the enemy arrives—the wrathful spirits of the Wingraves—and they crush him.

But James refuses to let this be interpreted as a triumph of death. Instead, Owen triumphs through sacrifice. Like a Christ-figure entering his Garden of Gethsemane, he willingly embraces his fate, proving his character in a way his family cannot comprehend. His destruction is the cost of exposing the corruption of their values. “Owen Wingrave” may be James’ most layered short ghost story. Beneath its gothic trappings lies a parable about the relationship between youth and tradition, idealism and heritage, pacifism and militarism. James wrestles with troubling questions: What is lost when we urge our youth to replicate the violent patterns of the past? What beauty and promise are wasted when innocence is judged inadequate merely because it is young? Are we justified in perpetuating ancient models of honor, or do we smother something rare and vital in the name of tradition?

The story leaves us with no easy answers—only the image of a young man walking deliberately into the chamber of doom, embodying both resistance and compliance, tragedy and triumph. In this paradox lies the enduring power of Owen Wingrave: a ghost story that is at once a critique of militarism, a meditation on manhood, and a timeless elegy for the youth sacrificed on the altar of history.