Bram Stoker's The Judge's House: A Detailed Summary and a Literary Analysis

- M. Grant Kellermeyer

- Oct 17, 2018

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 11, 2024

Unquestionably, “The Judge’s House” is Stoker’s short fiction masterpiece. Alongside “The Squaw,” “Dracula’s Guest,” and “The Burial of the Rats,” it will remain remembered and celebrated as one of his greatest literary accomplishments. A frequent luminary of horror anthologies, it has become as ubiquitous to editors as “The Body Snatcher,” “The Monkey’s Paw,” “Man-Size in Marble,” “The Signal-Man,” or “The Red Room.” It probes themes common to Stoker’s fiction, but still relatively marginal in Victorian fiction writ large, and plunges into a disturbing analysis of the perils of self-isolation, self-reliance, and intellectual hubris, challenging the Victorian ideal of the scientifically minded, self-reliant male hero. This is “Sherlock Holmes” meets “The Haunted House” – and in this instance, the hero’s Holmesian sangfroid prove utterly useless. The judge in question – patterned off of the infamous “Hanging Judge” Lord George Jeffreys – is as menacing and sensual an antagonist as Count Dracula himself – the sort of character we long to hear more from. Since its publication as a Christmas ghost story, it has remained a fixture of horror fiction and attracted a cult following.

It must be admitted that the story (like “Dracula” itself) is a virtually plagiaristic retooling of two of J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s best stories: “Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street” and “Mr Justice Harbottle.” Both stories (the second is a kind of prequel to the first) revolve around a house which is haunted by the malevolent spirit of a Georgian hanging judge. The first story is the more precise model of “The Judge’s House”: it includes two overworked students renting a cheap house, horrible nightmares, a giant anthropomorphic rat (the dead judge’s squealing reincarnation), a haunted portrait of the previous owner, and the hideous sight of the judge casually coming towards one of the young renters with a noose in hand. Le Fanu’s story was written in 1853, nearly forty years prior, and Stoker – to his credit – breathes new life into it by changing the tense from first person to third, by reducing the protagonists from two skeptical students to one, by changing the setting from the heart of Dublin to a remote manor, and by ending the story with a tragedy. Le Fanu’s fiction typically viewed humanity with cynicism, but also somber pity: the mass of men are like so many flies finding themselves trapped in webs woven by a disinterested creator – a punishing, merciless, vindictive God who has little interest in rewarding acts of righteousness, focusing all of his energies on reprimanding the slightest misstep, and bringing the full force of karmic punishment to bear against the merest accident of a sin.

Throughout the 1890s, Stoker committed himself to creating a similar literary perspective, and this manifests in most of his greatest works: lone male characters are beset by indefatigable enemies because of a slight mistake they have made and must be punished for. “The Burial of the Rats” features a protagonist whose sin is straying out of his socio-economic zone, while “The Squaw” shows the gruesome destruction of a man who accidentally killed a kitten, and in “Crooken Sands” an Englishman’s pompous decision to don a Highland costume during his Scottish vacation leads to his stumbling into quicksand. In “The Judge’s House” the sin is one which was intimately familiar to M. R. James (more on that later): arrogant intellectualism, the hubris of youth, and the arrogant self-isolation of the smugly self-reliant. It is a petty crime that requires an inordinately heavy price.

SUMMARY

Stoker follows a skeptical young scholar – the Jamesian introvert Malcolm Malcomlson – who rents a cavernous, Jacobean manor and demands privacy, spurns company, and rejects the help of friendly locals. Studying for his final math exams, the reason-obsessed graduate student takes the house because of its lonely situation and the locals’ aversion to it. He learns that his house was once owned by an impulsive hanging judge (his emotional foil), and that it is believed to be haunted. His skeptical indifference worries the local doctor – an open-minded skeptic – who believes that the isolation is wearing on Malcolmson’s sanity, and pleads with him to alert him at once if the scholar needs assistance by ringing the house’s ancient bell.

Disturbed only by the many rats (one of which is strangely anthropomorphic), he is gradually exposed to a world of supernatural horror that defies all of his logic, reason, and skepticism – one where anarchy, impulse, lust, and emotion dominate, where science is neutered, rationalism declawed, and the combined judge, jury, and executioner is the personification of chaos. At first it is just the scuttling of rats behind the wainscoting, but eventually they sally forth into the room with him, led by an enormous, ugly rat with eerily sentient features. Malcolm notes the similarity of this scowling vermin to the painting of the judge hanging on the wall, but passes this off as foolishness. Increasingly pestered by the rats, he hurls his mother’s Bible (the one book in his massive collection which he never pores over) at the rat’s leader, which momentarily frightens it, but the rats return in force later.

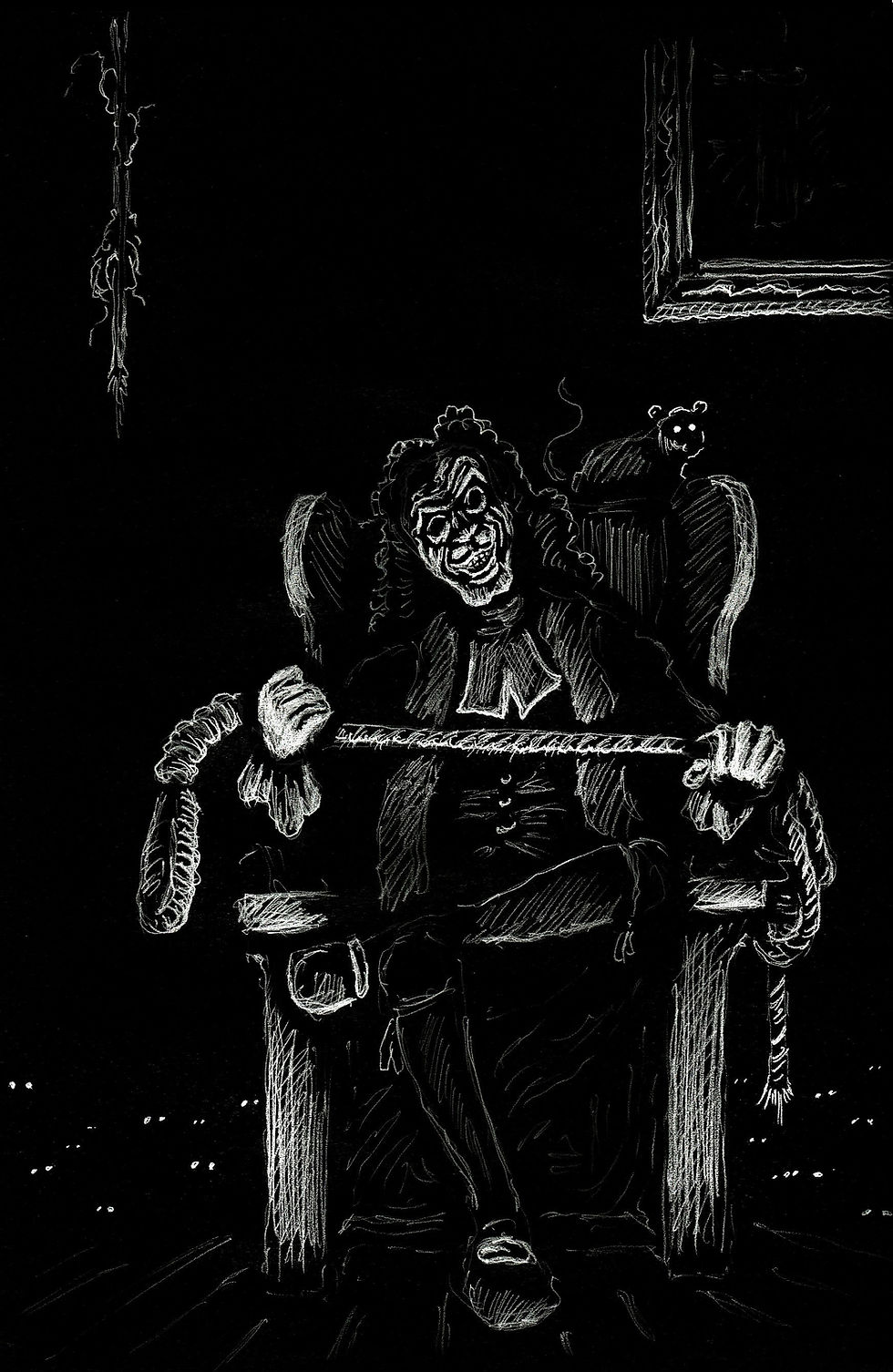

As the tension mounts and Malcolm’s isolation increases, he suddenly realizes that the portrait of the judge has been vacated: only bare, dry canvas is left where the figure once stood, and in a moment of horror he sees the leering, lusty judge eyeing him from the comfort of an easy chair. The rats on the floor start jumping for the bell rope (fashioned from the Judge’s old noose), trying to sound the alarm (we now realize that they are likely the captive spirits of his victims), but the Judge quickly cuts the rope and fashions a noose out of the slack. Overwhelmed by horror and awe, the converted skeptic initially tries to run, but his will is overwhelmed by that of his powerful captive, who ties the noose back to the bell pull, fixes it around his victim’s throat, and launches him into death. Sent running by the sound of the tolling bell, the villagers find Malcolm’s corpse bobbing from the noose, while the Judge’s portrait watches on – his face twisted in a sneer…

ANALYSIS

“The Judge’s House” simultaneously pays homage to J. Sheridan Le Fanu and prefigures the malevolent ghosts of M. R. James. James was potently inspired – like Stoker – by Le Fanu, and – like Stoker – used Le Fanu’s parody of Judge Jeffreys in his fiction. Jeffreys himself appears in “Martin’s Close” as a character, where he prosecutes the murderer of a mentally challenged woman whose ghost stalks him, and is referenced in several other tales. The general plot of “Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street” (and it’s prequel “Mr Justice Harbottle,” and “The Judge’s House”) is appropriated into several of James’ most chilling stories: “The Mezzotint” (a haunted picture comes to life), “The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral” (an ambitious scholar moves into a house where he is gradually stalked by predatory spirits who gradually materialize and kill him), and “Oh Whistle and I’ll Come to You My Lad” (a young skeptic is hounded by a leering specter who challenges his arrogant understanding of reality) among others. James, Le Fanu, and Stoker all delighted in two particular horror tropes that shine through “The Judge’s House”: the predatory revenant who is grotesquely physical and overwhelmingly malicious, and the self-reliant, antisocial, introvert who prefers lonely independence to human community. All three men seem to have written from personal experience as bookish loners, and all three delighted – almost sadistically – in torturing their victims for the hubris that they arguably suffered.

Few of their victims are more viciously and needlessly punished (perhaps with the exception of James’ Paxton in “A Warning to the Curious”) than Malcolm Malcolmson. As his redundant name implies, he is self-sufficient, generating his own sense of identity, following his own code of values, and spurning the collective identities of family, community, or religion. Cynical, antisocial, and independent, he worships the skeptic’s trinity of Science, Reason, and Logic, but meets his match in the Judge – a savage man who is the apotheosis of chaos, impulse, and caprice. The Judge is renowned for aggressively ordering executions on emotional whims (Stoker describes it as “judicial rancour”), and experiences life – not with logic or reason – through the arousal of his senses. He is a very sexualized ghost, one which takes lavish delight – an almost orgasmic pleasure – in inspiring fear and mastering his victims. Like Christopher Lee’s Judge Jeffreys in The Bloody Judge, or Vincent Price’s eponymous Witchfinder General, he seems to seek and gorge on sexual pleasure through the medium of judicial power. Hence – should we read this as a parable – logic is mastered by emotion, reason by caprice, science by spirit, and rationality by impulse.

Many have made the argument that Stoker was a repressed bisexual, and while I won’t plumb too deeply into their reasons and the merits of those reasons, it is noteworthy to see how Stoker pits the sensual master against the repressed submissive. He revisits these BDSM themes in “The Squaw” where a main character relishes the idea of being bound and placed in an iron maiden with barely cloaked sexual thrills, and again in Dracula where Harker finds himself made submissive to the sadistic female vampires. Sexuality as a whole disturbed Stoker, and it was a recurring theme in his fiction, representing all that is beyond human control and understanding – all that is impulsive, emotional, sensual, and primitive. Like James and Le Fanu, he delighted in juxtaposing intellectual smugness and logical rationality against the primal ugliness of the human spirit. All three men wrote stacks of stories that featured this exact showdown, and all three excelled at demonstrating the weaknesses of cool intellectualism in the face of unconquerable nature. There are few characters in literature more dismissive of those sensations than Malcolm Malcolmson – the ultimate skeptic and materialist – but there are equally few characters in literature that better embody them than the Judge. When they finally meet – rationality and sensuality, logic and caprice – Stoker doesn’t give Malcolmson a fighting chance – a telling moral.