Mary Elizabeth Braddon's The Cold Embrace: A Detailed Summary and a Literary Analysis

- Michael Kellermeyer

- Nov 6, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 11, 2024

We are continuing to celebrate Oldstyle Tales’ 10th anniversary during the month of November by highlighting rarely commented upon tales from our very first publication, The Best Victorian Ghost Stories, which was first released on Halloween, 2013. This week’s episode is Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s relentless, feminist revenge fantasy, “The Cold Embrace…”

The typical ghost story in Victorian Britain followed this formula: a misdeed is done, often secretly, and the truth is not exposed until a supernatural agency intervenes – either to assist a third party in uncovering the wrongdoing, or in personally tormenting the malefactor. The following, then, is a typical Victorian ghost story in plot. But in execution, it is surpassingly excellent. Writing in an aggressive present tense, Braddon generates a slow-burning terror that exponentially increases after the tale’s tragic midpoint. Several masters of the ghost story appear to have been entranced by her plot of emotional neglect and supernatural comeuppance: Algernon Blackwood modelled two stories after it – “The Tryst” (which follows a cavalier fiancée who goes abroad and returns years later for the woman he assumed would be waiting for him) and “The Dance of Death” (which closely follows Braddon’s chilling dance hall climax) – Mrs J. H. Riddell used it as the basis for one of her finest stories – a violently erotic tale of murder and class disparity called “A Terrible Vengance” – and M. R. James’ flesh-prickling “Martin’s Close” is so similar in nature that it is better to let you read this story without further comment.

SUMMARY

The story concerns the fate of an attractive but arrogant German artist. He was “young, handsome, studious, enthusiastic, metaphysical, reckless, unbelieving, and heartless,” and we are told that “such things as happened to him happen sometimes to artists [and] Germans,” and that – for all his cruel vanity, in fact as a consequence of it – he was adored by a young woman. The woman in question was his cousin Gertrude, who had idolized him since he was orphaned and adopted by her father, his paternal uncle.

We are told that initially the artist loved Gertrude back, but that over time his affection became “wretched and threadbare” in his “selfish heart.” They hid their romance from her father and wandered the streets of Antwerp while he was apprenticing there to a Belgian painter, and one night the young man proposed to her with a ring in the shape of an ouroboros (a snake devouring itself): “the symbol of eternity.” Although her fiancé is a devout atheist, he is an “enthusiastic adorer of the mystical,” and declares:

'Can death part us? I would return to you from the grave, Gertrude. My soul would come back to be near my love. And you--you, if you died before me--the cold earth would not hold you from me; if you loved me, you would return, and again these fair arms would be clasped round my neck as they are now.'

She, however, is more pious, and urges him to recant his words because the only people, she believes, who are able to haunt the living are those who die in despair, outside of peace with God, and doesn’t wish either of them to suffer this fate.

Dismissing her quaint piety, the artist goes off to Italy to study the old masters and their engagement remains a secret. At first his letters are frequent, then fewer, then cease altogether. She tries to rationalize his inattention, but gradually falls into despondency as she wonders why she has lost his love. In the meantime, her father arranges for her to marry a wealthy suitor – unaware of her prior engagement and determined for her to marry an aristocrat – and she finds herself overwhelmed with anxiety.

Desperate to escape her predicament, she writes a letter to the artist begging him to return to her, to marry her, and to take her far away. But days go by, her wedding day approaches, and no response comes. She pleads with both her father and her wealthy fiancé, but neither are willing to let her delay the wedding any further, and she doesn’t have the heart to tell them the truth. The night before, she walks to the bridge where she and the artist became secretly engaged and peers into the dark water…

***

The morning after, the artist returns with her letter in hand, but he isn’t eager to see her: he has been having an affair with one of his Italian models, and, after all, Art itself was “his eternal bride, his unchanging mistress.” Indeed, he is glad to hear of her engagement, especially since the suitor is so wealthy: “good; let her marry him; better for her, better far for himself. He had no wish to fetter himself with a wife.” His only object in returning is to congratulate her and close this chapter in his life for good.

Walking towards the bridge he encounters a party of fishermen gingerly bearing something they have found in the river. It is, he learns, the body of a suspected suicide: a beautiful woman. He cheerily remarks that suicides are always beautiful and pulls out a sketchpad to make a quick portrait of the victim. Of course, however, he is stunned to find himself leering upon Gertrude’s pale face. Looking her over, he is ashamed to find her still wearing his serpent ring, and is mortified – mystic that he is, regardless of his dismissive atheism – at the memory of his promise that death would not be able to keep them apart.

He flees from the corpse and the city, not resting until he is miles away, where he and his pet dog sit down on the roadside to catch their breath. Despite all of his efforts, he cannot banish the memory of “the corpse covered in damp canvas” from his mind. A coach pulls up and he and the dog climb aboard, bound for Cologne where he hopes to pour himself into his studies.

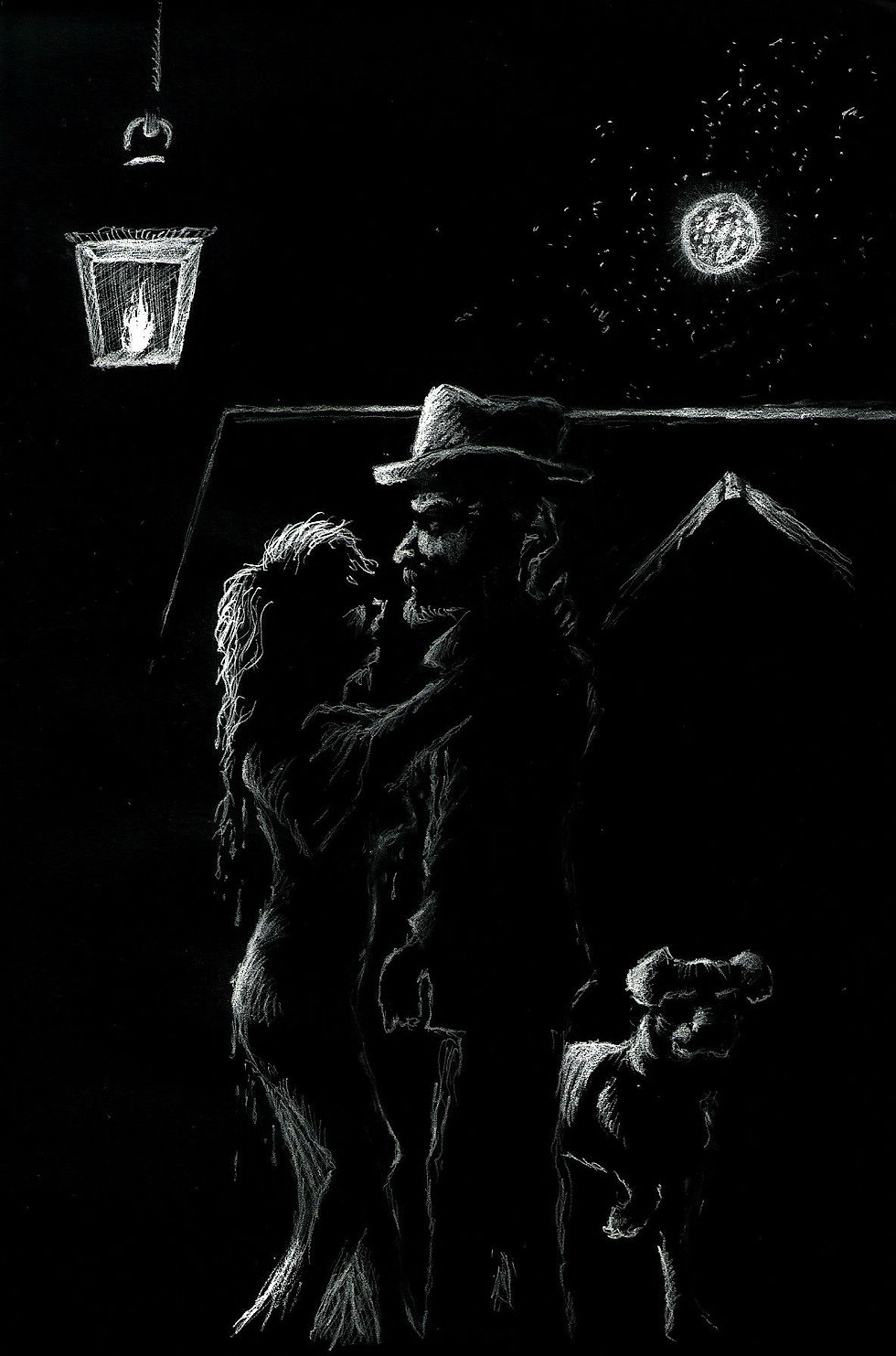

While there, he smokes heavily, sings college drinking songs, and finally forgets his dead lover’s face. One night, though, as he and his dog are admiring the way the moonlight is hitting the cathedral, he is stunned when: “Suddenly some one, something from behind him, puts two cold arms round his neck, and clasps its hands on his breast.” Glancing to the side, he sees his shadow and his dog’s but no one else’s. He turns around, and – though he can still feel the clammy touch on his neck – finds himself utterly alone:

“He tries to throw off the cold caress. He clasps the hands in his own to tear them asunder, and to cast them off his neck. He can feel the long delicate fingers cold and wet beneath his touch, and on the third finger of the left hand he can feel the ring which was his mother's--the golden serpent--the ring which he has always said he would know among a thousand by the touch alone. He knows it now!”

Desperate to be ridden of this revolting touch, he calls his dog to him, and the big hound puts his forepaws on his chest, but immediately recoils in fear from his master. But this seems to have helped: the cold embrace dissipates, and he runs back to his apartment. From that day on, he surrounds himself with company, takes on a roommate, and fills his calendar with activities, refusing to be alone, but during those inevitable moments when he must cross an empty street, he “feels the cold arms around his neck” again, and eventually he flees Cologne entirely.

***

Low on money, he travels alone, and it becomes “a common thing for him to feel the cold arms around his neck.” A year goes by and he finds his way to Paris, hoping to revive his spirits when the famous Carnival begins, with his crowds and jolliness. He attends the Carnival celebration at the Paris Opera, using what little money he has to rent a domino costume. He is delighted to find “no more darkness, no more loneliness, but a mad crowd, shouting and dancing,” and – what’s more – he meets an alluring young woman there – dressed in a revealing, cross-dress costume – who comes onto him and stays close to him throughout the dance.

The two pour themselves into wild debauchery, dancing wildly with abandon, and – over time – he notices people talking about the “outrageous conduct of a drunken student.” He knows that they are referring to him, but is stunned: he hasn’t had anything to eat or drink for days. Still, he parties on, late into the night and early into the morning. Eventually, the candles go out, the revelers slither home, and silence surrounds him. The female crossdresser’s arms around his neck become heavy like lead, and in the pale, grey light proceeding the dawn, he notices a change coming over her:

“And by this light the bright-eyed [crossdresser] fades sadly. He looks her in the face. How the brightness of her eyes dies out! Again he looks her in the face. How white that face has grown! Again--and now it is the shadow of a face alone that looks in his. Again--and they are gone--the bright eyes, the face, the shadow of the face. He is alone; alone in that vast saloon.”

Alone in the dark, with no music to quiet his thoughts, he feels terror overwhelming him. And there they are: the cold arms once again pulling down on his neck as if for a kiss: “they whirl him round, they will not be flung off, or cast away; he can no more escape from their icy grasp than he can escape from death.” His cannot call for help – his throat is too dry – and “the silence of the place is only broken by the echoes of his own footsteps in the dance from which he cannot extricate himself.” Finally, he gives into the embrace and clasps her back, eager to have one last dance that night, even if it’s the last thing he does...

Half an hour later a patrolman comes to inspect the dark dance hall and is followed by a large, howling dog who has been waiting uneasily on the steps, afraid to go inside. There man and dog find the corpse of an emaciated German artist – dead from an aneurism which is attributed to starvation.

ANALYSIS

Edgar Allan Poe often followed the doomed relationships of emotionally complex women, and the insensitive geniuses who saw them as a fixed, artistic ideal. These men hoped to divorce the spirit (beauty, poise, affection) from the body (needs, mortality, subjectivity) by objectifying their lovers and ignoring or denying their emotional and physical dynamism. This story, which closely follows Poe’s model (cf. “The Oval Portrait,” “Ligeia,” “Morella,” “Berenice”) ponders another favorite theme of America’s master of philosophical horror: the tenuous balance between the physical and the psychical – mind and matter, spirit and self.

The German artist exalts the spirit, but denies the body – he lavishes on his lover’s ideal form, but neglects her complex needs as a living person. He approaches the world as if it were all art and no reality, and it is telling that he dies from “want of food, exhaustion” – by mistreating his own physical and mental needs, he forfeits life for pretense, and becomes yet another victim of his one-dimensional view of people.

Careless, insensitive, and emotionally stunted, he serves as a warning to men who imagine that negligence of a lover is a small matter. Women are dynamic and complex, Braddon warns her readers (ever urgently in her pulsing present tense), and while the ramifications of a jilt may not be swift in coming, a neglectful lover should always beware the consequences of his abuses: the man who spurns a tender kiss may find himself drawn into an un-relinquishing embrace.